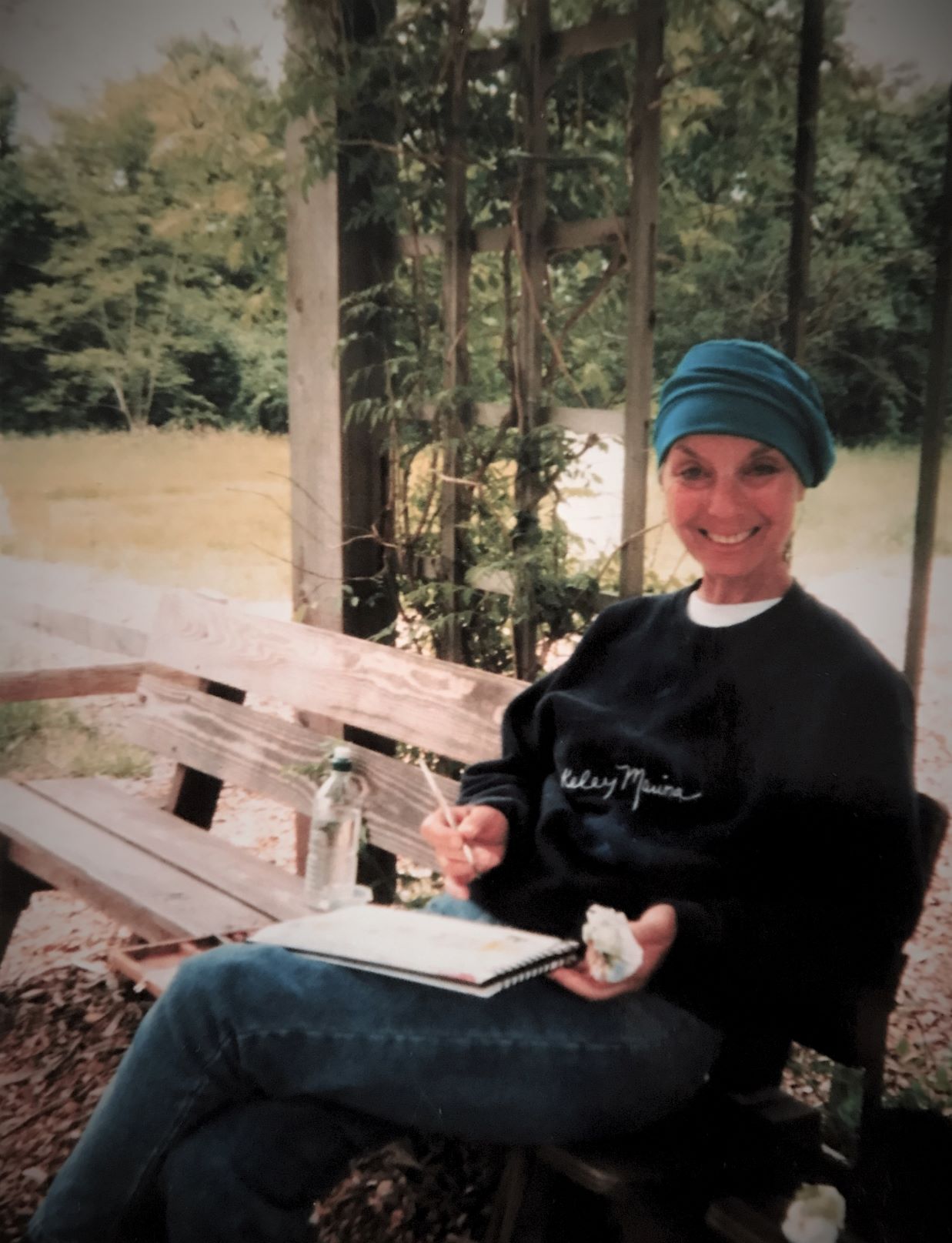

Ruthellen’s Story

Our mother was Ruthellen Pollan, a radiant spirit, prolific painter, and energetic ball of creativity that she rolled across the panorama of her rich, textured, and inspiring life. She celebrated her exuberance for nature through Monet’s gardens in Giverny, France, the harbors of her native Long Island, and the sweeping vistas of Bear’s Ears, Moab, Canyonlands, and the Monument Valley of her adopted Utah earth and sky.

Ruthellen’s journey had no dead-ends or straight lines. Her best girl pal Jackie remembers how mom used to color outside the lines. The lines weren’t rules or directions — just someone else’s version of a contour or a boundary. Nor was there any prescribed master plan plotting out her life’s works.

Coloring Outside the Lines

Her working class parents appreciated the arts and nurtured their daughter’s interest and talent through art classes, music lessons, and museum trips into Manhattan. If Queens wasn’t exactly the fast lane to the limelight, her artistic gifts were cultivated to one day enter that world. Ruthellen’s imagination was

the only pre-requisite. Her originality was a given. No one taught her that.

When Ruthellen decided to follow her bliss, the road less taken was the only option if she was to follow her true calling. It was both journey and manifest destiny. She set on a path of renewable abundance — the natural beauty of this world and her own formidable capacity for sharing in its celebration.

Her creative expression found root first in her drawings and paintings, then through her teaching of multiple mediums across every age and geography she encountered in her breathless 63 years. And the art too was constantly evolving:

- First through oils

- Then pen and ink

- Followed by pastels, and

- Full circle back to oils and acrylics.

Her Palette and the Truck Bed

Ruthellen’s first artistic loves were the impressionists. She felt and carried the romantic vibrancy of Boudin, Rousseau, and Monet. Their bold palettes played off the natural light of their en plein air magic, and so did hers. In fact, once Ruthellen was rooted in Blanding, the back of her ’95 Ford Explorer was either kenneling her dogs, stowing her easels, or hauling art supplies to campus.

Teaching in Southeastern Utah is no doubt the most improbable turn on the improbable Ruthellen roadmap. In 1990 she was making her scenic way across the country. Trying to restart her life, actually. What was her destination?

How about the Pacific Ocean for an ETA?

Ruthellen was never an as-the-crow-flies navigator — especially when she was mulling over big decisions like the unwritten chapters of her life. Her prior life (marriages, motherhood, Madison Avenue art galleries) was in the rear view. This was not just the latest chapter. Intermission was over. This was her second act. More on that later.

Earlier in her career she had aspired to gain professional recognition. And while her work was respected, praised, and collected, popular acclaim proved elusive. She found success in the trend-setting world of Madison Avenue difficult, but refused to abandon her vision.

She continued…

- Lining up the gallery showings

- Shipping epic landscapes to all corners of the country, and

- Marketing her work as reproductions for professional offices.

Imagining Without Limits

These were all on the to-do list of the prior life. Now she was dropping all that and starting fresh; her eyes firmly fixed to the horizon. And what she saw excited her every bit as much as Monet’s gardens. It was the freedom. It was expansive. And this new recognition was a continuation of her first love; her only choice. It was the grandeur of the canyons and majesty of the sky.

It was then that the open-ended nature of her westward getaway took on a whole new entrance ramp. A nail had punctured her tire. It happened on the Southeastern Utah section of her Four Corners destination that day. The nearest tow was in a town called Blanding. And as whimsical as this sounds, there was nothing fanciful about where Ruthellen’s attentions traveled then. Before the lug nuts were re-engaged, the following doors had been located, some even cracked open. She was playing for keeps:

- Inquiry of local education facilities (college-level preference)

- Initial on-campus site visit

- Personal introduction to leadership and staff

- Draft agenda for unscheduled meeting

RE: why an art program was the cross-cultural shot-in-the-arm.

That’s right. How an arts program connected with the College of Eastern Utah’s community mission — particularly the San Juan Campus’s sense of regional heritage and stewardship.

Without Apology

1996: The dream becomes the dream home

That realization wasn’t fully acted on before her flat was repaired. But Ruthellen’s what-the-heck agenda-setting found an unlikely champion in her future colleague and Dean, Bob McPherson. His embrace of her trailblazing proposal happened over months and semesters, not days and weeks. Over time, he brought together the planning, operational, and academic ranks of the college to steer and ultimately support this daring step in a new institutional direction.

The fact that the then CEU academic model drew from a vocationally-leaning fields of study is further credit to Ruthellen’s gumption for pitching such an untested venture to complement a well-established curriculum. She justified the arts — with unassuming passion and without apology.

She did so both in-sync with existing programs and on their own merit. The new art program would be inclusive of the region’s creative traditions. Young, aspiring artists would have a home here. She demonstrated art’s role in visual communication through promotional marketing and user interface design. She tied it to the graphical imagery and legacy that blankets the weaving, jewelry-making, basketry, and textile expressions of Navajo Nation.

Family Persuasion

Ruthellen’s powers of persuasion were tested in two ways: (1) by pitching an entirely new undertaking to her new, more conventionally-minded colleagues, and (2) by her own whimsical nature. This was her limitation to grasp the same gravitational realities the rest of us take for granted. The matter of the peach tree, for instance.

Ruthellen lost her mom and brother within several months before she too fell ill several years later. She decided that two markedly different plantings were required to celebrate their legacies and contrastable personalities. The spirit of her mom, Harriet, was embodied in the strong-willed and uncompromising trunk of a walnut tree. Erwin, however, was more pliable, easy-going: “a real peach” is how mom landed on the fruit tree as an appropriate tribute to her brother. The parched, mineral-dense Blanding turf surrounding her cultivations had other ideas. It was not nearly as forgiving as the namesake of the peach tree.

The Curtain Rises

The other heirloom that resonated greatly with Ruthellen was her family’s capacity for self-renewal. Her older brother Stephen was a prolific author of consumer finance, home buying field guides, and personal life scripts. One dominant theme throughout Stephen’s writing was the North Star of Ruthellen’s journey – the ability to reinvent one’s self well after all the familiar guideposts of marriage, career, and lifestyle choices had failed the test of experience. It was these hardships that informed the mid-course correction that Stephen titled “Second Acts.” Not surprisingly, he dedicated the book to his sister.

Ruthellen’s narrative was instructive not only on the professional but the personal level. The day of the flat tire marked the retreading of Ruthellen’s life footing. She was marshalling her passions, experience, and job skills, and molding something entirely new from the chalky, windblown building blocks of the Utah desert valley basin.

Dad

The first and last love of Ruthellen’s short time with us was her father, Robert. She was the apple of his eye from day one. There was no music lesson, art class, or form of self-expression that Robert didn’t make part of his daughter’s extra-curricular calendar. Many years later after Harriet had passed, Robert knew exactly where he needed to be and who he needed to be with. There was never talk of nursing homes or assisted living for 94 year-old Bob. Coming out west to live with Ruthellen was to some extent the first presenting of the Ruthellen Pollan Scholarship.

The recipient had his ticket punched for art school — full room and board. The moment had been waiting for arrival since Ruthellen gave Bob his first art show at South Huntington Library as a retired liquor salesman. The title of that show was memorable and sustaining as a theme and a credo. She called it “Late Bloomers.” And the blooms never left the roses.

When Harriet passed on, the attentive Eagle Scout husband vanished. In his place appeared a spirit free to be sculpting, painting, and hanging with Ruthellen, the dogs, and whoever else wandered in. Mom was too happy not to oblige. Her home was her dad’s home.